Notifications

ALL BUSINESS

COMIDA

DIRECTORIES

ENTERTAINMENT

FINER THINGS

HEALTH

MARKETPLACE

MEMBER's ONLY

MONEY MATTER$

MOTIVATIONAL

NEWS & WEATHER

TECHNOLOGIA

TV NETWORKS

VIDEOS

VOTE USA 2026/2028

INVESTOR RELATIONS

DEV FOR 2025 / 2026

ALL BUSINESS

COMIDA

DIRECTORIES

ENTERTAINMENT

FINER THINGS

HEALTH

MARKETPLACE

MEMBER's ONLY

MONEY MATTER$

MOTIVATIONAL

NEWS & WEATHER

TECHNOLOGIA

TV NETWORKS

VIDEOS

VOTE USA 2026/2028

INVESTOR RELATIONS

DEV FOR 2025 / 2026

About Me

Latinos Media

Latinos Media Latinos Media provides all types of news feeds on a daily basis to our Members

Posted by - Latinos Media -

on - May 12, 2023 -

Filed in - Technology -

-

495 Views - 0 Comments - 0 Likes - 0 Reviews

This article is from The Checkup, MIT Technology Review’s weekly biotech newsletter. To receive it in your inbox every Thursday, sign up here.

Regular readers will know that the microbiome is one of my favorite topics to cover. The billions of bacteria crawling all over our bodies play a vital role in our health, influencing everything from digestion to immune health and even our moods.

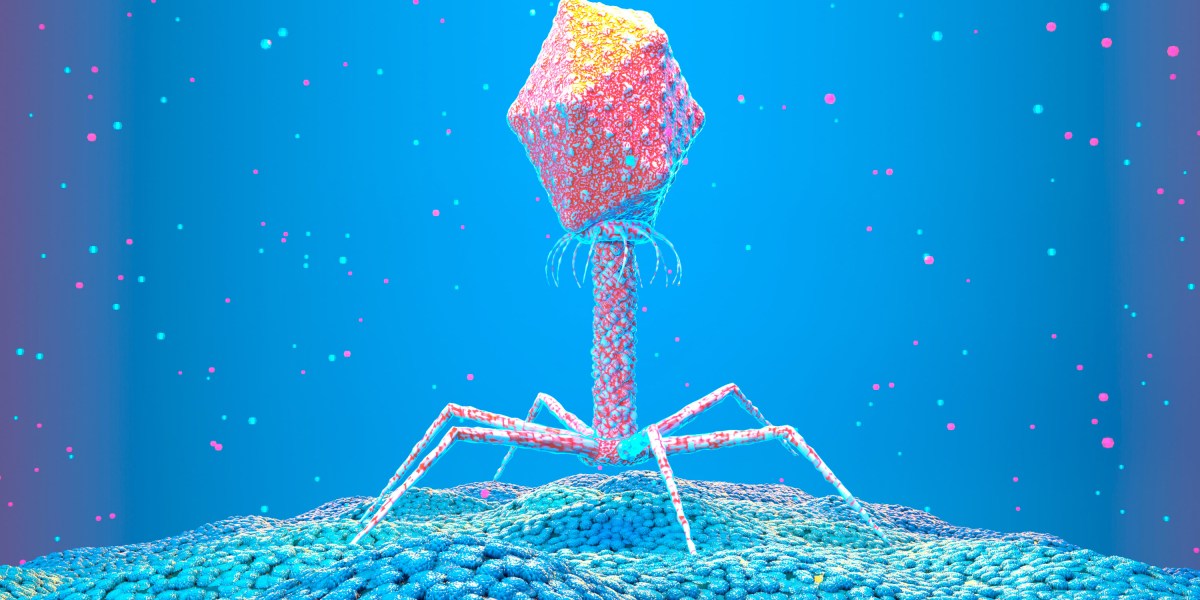

But there’s something else that makes a home inside us. Bacteriophages—or phages for short—are microscopic viruses even smaller than our gut microbes. These viruses infect bacteria and turn them into factories to make more of themselves.

Phages were discovered over a hundred years ago, and a small band of scientists quickly realized their potential. Because these viruses can kill bacteria, they could potentially be used to treat a whole host of nasty bacterial infections.

Within a few decades of their discovery, they were largely abandoned in favor of antibiotics. But as antibiotics increasingly fail us, and the deadly threat of antimicrobial resistance looms large, interest in phage therapy is on the rise. We’ve still got a lot to learn about phages, though, and we’ll have to overcome our hatred of viruses before phage therapy becomes mainstream. After all, would you drink a vial of virus?

“There’s an ick factor,” says Chloe James, a microbiologist who studies phages at the University of Salford in the UK.

Phages are different from the viruses that infect us, such as the ones that cause flu, Ebola, or covid. Instead, phages specifically infect bacteria. The two have evolved alongside each other—wherever there are bacteria, you’ll find phages infecting them.

In fact, you’ll find phages almost everywhere you look. “They are incredibly diverse, and they’re the most abundant organism on the planet, so they’re literally everywhere,” says James.

Many phages work by landing on a bacterium and injecting their own DNA inside it. There, the DNA can replicate. Eventually, the bacterium itself will burst, emitting an explosion of phages. Not all phages work this way, though. Some insert their genes into the DNA of bacteria. This might stop the bacteria from being able to replicate, or it could give them other powers, such as the ability to cause a more deadly disease or to resist the effects of antibiotics.

It’s complicated, partly because there are so many phages, and partly because they all appear to be incredibly specific. They’ll only infect particular strains of bacteria, for example. But find the right phage for the right bug, and the potential for phage therapy is huge.

Multiple citizen science projects are underway to encourage people to explore the phages all around them, whether they be lurking in garden soil or in the compost bin. And while most of the phages being catalogued in biobanks are collected from wastewater, some of the viruses collected in people’s homes have already proven to be exceptionally useful.

In 2010, Lilli Holst, an undergraduate student at the University of KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa, took part in a project designed to encourage students to find phages. She decided to look in her parents’ compost bin, among other places. A scraping from the underside of a rotting eggplant turned out to contain a phage that was entirely new to science. She called it Muddy.

This phage was found to be able to kill a type of bacteria that can cause particularly nasty diseases. When, almost a decade later, a teenager in London came down with an aggressive, multi-drug-resistant infection following a double lung transplant, doctors gave her a 1% chance of survival. In a last-ditch attempt to save her life, doctors injected her with Muddy, along with two other genetically engineered phages. She began to recover within days and left the hospital a few months later. Muddy has been used to treat over a dozen people in the years since, as I learned in Tom Ireland’s forthcoming book The Good Virus.

Finding the right phage for the job won’t always be straightforward. But scientists are working on alternatives. We might be able to engineer phages, for example, providing them with the genes they need to infect the specific bacteria we want to kill. It might also be easier to make use of the chemicals phages make, rather than the viruses themselves. Phages make enzymes that rip holes in the walls of bacterial cells, bursting them open. We might be able to treat people with those specific enzymes, says James.

Now it seems the time is right for phages to make a return to the spotlight. Antimicrobial resistance is on the rise; it already plays a part in millions of deaths every year. In the UK, an ongoing government inquiry is exploring whether phage research should get more state funding. Over 30 active clinical trials of phage therapies are listed at a US-run trial registry. And Ireland’s book making the case for phages is out this summer.

Once research does make more headway, there’s another challenge to overcome. The idea of intentionally putting viruses into your body is not a particularly appealing one for most people.

Having said that, bacteria have benefited from great PR in recent years. Most of us know the benefits of a healthy gut microbiome, and many people happily chug down bottles of bacteria they buy in supermarkets. Can viruses win us over too?

“We need to stop being so afraid of phages and see what they can do for us,” says James.

Read more from Tech Review’s archive:We can use wastewater to track the rise of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, as we covered in a previous edition of The Checkup.

Antimicrobial resistance is one of the greatest health threats of our time. We could use what we learned from the covid pandemic to tackle it, Maryn McKenna wrote in this piece from 2021.

It’s not just viruses—scientists are also exploring whether genetically engineered bacteria could be used to treat diseases like cancer.

Microplastics are messing with the microbiomes of seabirds. That raises the question of what these ubiquitous materials might be doing to the microbes living inside us, as I reported a couple of months ago.

Microbes have plenty of other potential uses, too. Some companies are trying to use them to make greener aviation fuels, for example, as my colleague Casey Crownhart reported last year.

From around the webThe only UK team allowed to use technology to create embryos with DNA from three people has been extremely tight-lipped about its trial, which has been running for the last five years. But a freedom of information request to the UK’s Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority has revealed that “less than five” babies have been born in the UK using this approach. A spokesperson for the team has said it is unable to comment as its write-up is being peer-reviewed. (The Guardian)

A new map of the human genome could explain the DNA that makes each of us unique. The pangenome, as it’s called, has been 10 years in the making. (MIT Technology Review)

Pain and fear are inextricably linked. Research in mice hints that targeting memories in our brains could help treat chronic pain. (Nature Neuroscience)

Should breast cancer screening begin at 40? The US Preventive Services Task Force believes so, according to new guidelines released earlier this week. But many doctors and scientists disagree. (STAT)

Researchers are attempting to use gene editing technology to improve the flavor of vegetables. Apparently not everyone likes the taste of kale … (Scientific American)