In 2020, spending on specialty drugs was $265 billion; this constituted 49.6% of total prescription drug expenditure. To combat rising costs, payers have turned to white, brown and clear bagging as well as approaches to restrict the site of care where patients receive specialty drugs. What are these “bagging” policies, what are the pros and cons, and what legislation has or is considered being passed to restrict payers ability to implement these programs. Today, I summarize a white paper from ICER titled “White Bagging, Brown Bagging, and Site of Service Policies: Best Practices in Addressing Provider Markup in the Commercial Insurance Market“. This post follows up my previous post on the topic two years ago.

Definitions

-

White bagging policies deliver drugs from specialty pharmacies directly to providers at the site of service where the drug will be administered (typically a physician’s office, HOPD, or home infusion provider). Providers are responsible for receiving the drug delivery from the specialty pharmacy, unboxing it, and storing it until the patient is on site and ready for administration. The moniker “white bagging” arises from the “white coats” of the providers who receive the drug from the specialty pharmacy. Analysis of the impact of white bagging on payers and patients will be discussed later in this paper.

-

Brown bagging policies require patients to pick up their prescribed clinician-administered drugs at a specialty pharmacy or have these drugs delivered directly to patients, after which patients are responsible for storing these drugs appropriately until the time of their appointment with a clinician, at which time patients bring their drug with them to hand over to a clinician for administration. The term “brown bagging” comes from the analogy to a “brown bag” lunch carried by an individual.

-

Clear bagging involves a provider, typically a hospital, creating a formal program through which its internal specialty pharmacy can dispense the drug and deliver it to the site of service. Clear bagging thus serves as a provider strategy to offer an alternative to white bagging and brown bagging, thereby retaining the revenue associated with specialty drug delivery. Clear bagging also avoids some of the logistical and safety challenges associated with white bagging. For instance, if a patient’s drug dosage needs to be adjusted, the hospital specialty pharmacy can dispense the new dosage and have it delivered to the on-site hospital suite or clinic without having to reschedule the patient’s appointment as can be the case with white bagging. There has been a recent proliferation of hospital-owned specialty pharmacies, with estimates from 2019 showing that 26% of hospitals owned a specialty pharmacy.

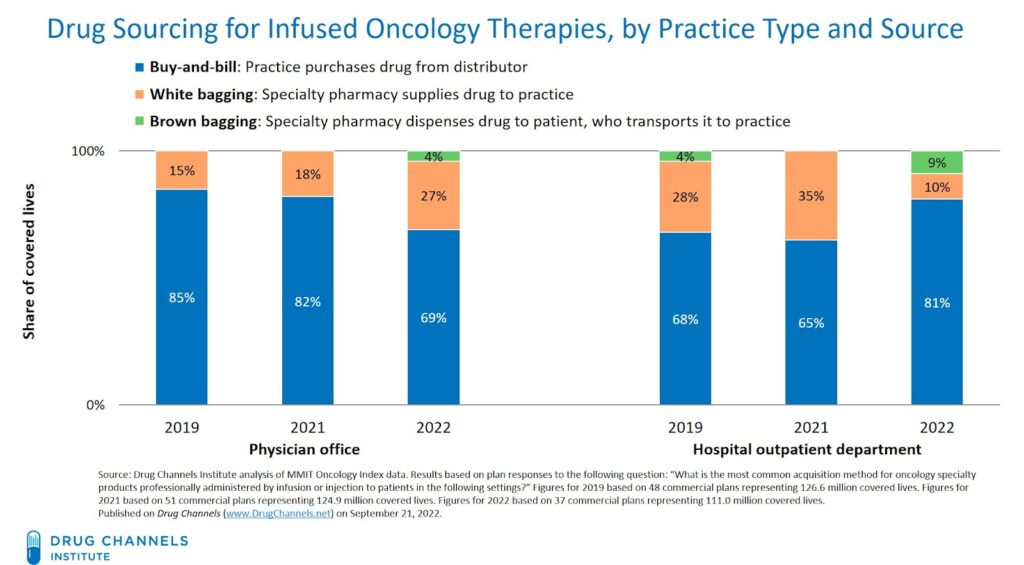

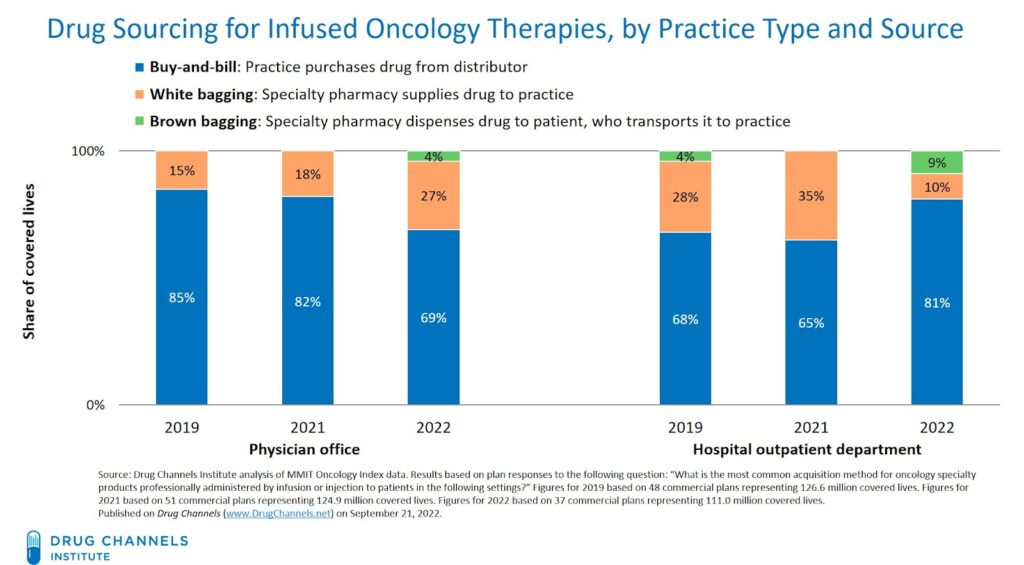

How common are these practices? Well, as of 2022, 27% of oncology therapy products administered in physician offices under commercial insurance were subject to white bagging policies. Part of this is driven by industry consolidation.

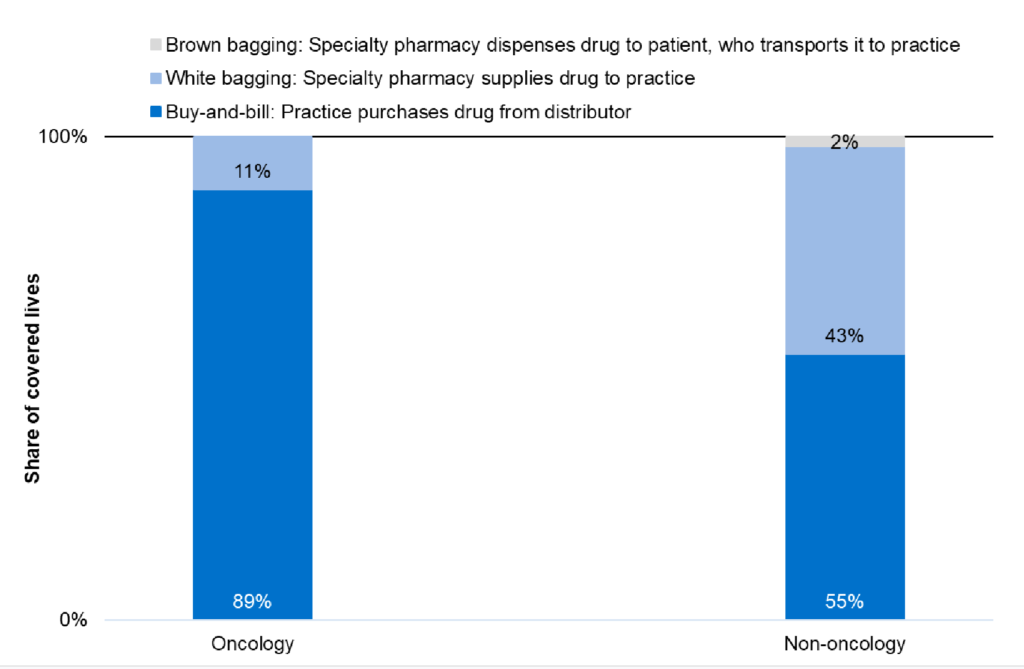

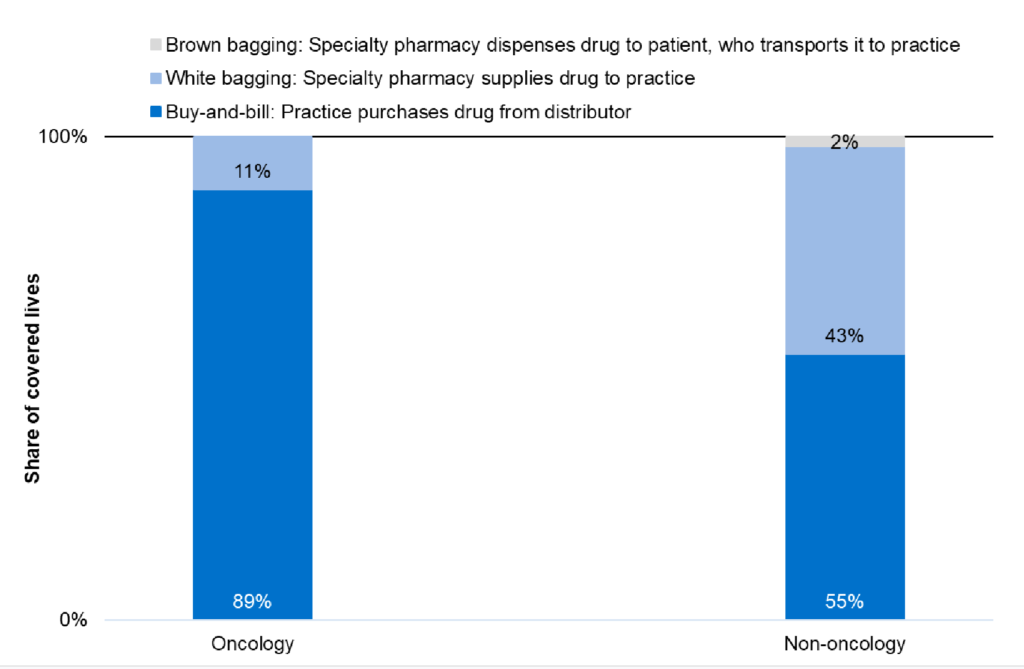

It is even more common among non-oncology products as shown from data as of 2019 below.

Part of the reason for increased ‘bagging’ policies has to do with industry consolidation.

the three biggest PBMs aligned with payers –CVS/Aetna, Optum/UnitedHealthcare, and Express Scripts/Cigna — accounted for 77% of all prescription claims.36,37 Some providers assert that bagging policies are motivated by the health plan’s desire to drive volume to their own specialty pharmacies.

Restrictions on site of service intended to move patients to lower cost sites of care are also becoming more common. According to one survey:

…by 2020 almost 70% of commercial plans had site-of-service programs, of which 34% were mandatory and 32% were voluntary.24 That same survey found that across all site-of-service strategies, commercial payers had shifted 30% of members into home infusion, 19% to ambulatory infusion suites, and 14% to independent physician offices in 2019.

Key criticisms of white and brown bagging are:

-

Patient safety. For brown bagging in particular, patients may not appropriately administer these specialty drugs at home. Also, with long travel times, drugs may spoil if not kept properly refrigerated.

-

Impact on disadvantaged patients. For patients with limited transportation option, brown bagging may impose a burden on patients.

-

Incorrect prescriptions and difficulty changing prescriptions. In one survey, 66% of respondents said that they had received a product via white bagging that was no longer correct due to updated treatment course or dose being changed.

-

Patient out-of-pocket costs. Lower payers costs from white and brown bagging often are not passed on to patients. In fact, OOP costs may rise if drugs move from being part of the medical (i.e., physician administered) benefit to the patient’s pharmacy benefit.

-

Provider revenue. Providers–particularly 340B hospitals–may experience a significant loss in revenue as drug administration moves from hospital-based pharmacies to payer-owned/controlled specialty pharmacies.

-

Drug wastage. “Because drugs obtained via white or brown bagging are specific to an individual, as opposed to the buy-and-bill process whereby physicians purchase drugs to have in-stock, any excess drug in the white or brown bagged vial must be discarded and cannot be used for another patient, leaving the payer and patient responsible for the entire vial and associated cost-share.”

Similarly, criticism of site of services restrictions include: (i) increased patient travel burden, (ii) reduced oversight for adverse event monitoring, and (iii) negative impact on provider (especially hospital outpatient facility) revenue.

Legislative initiatives.

-

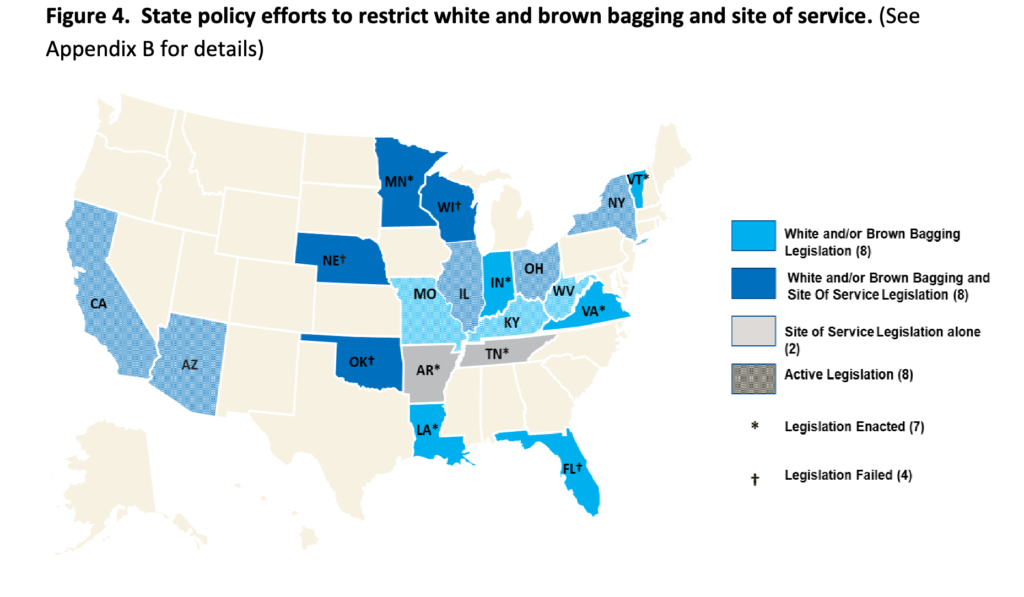

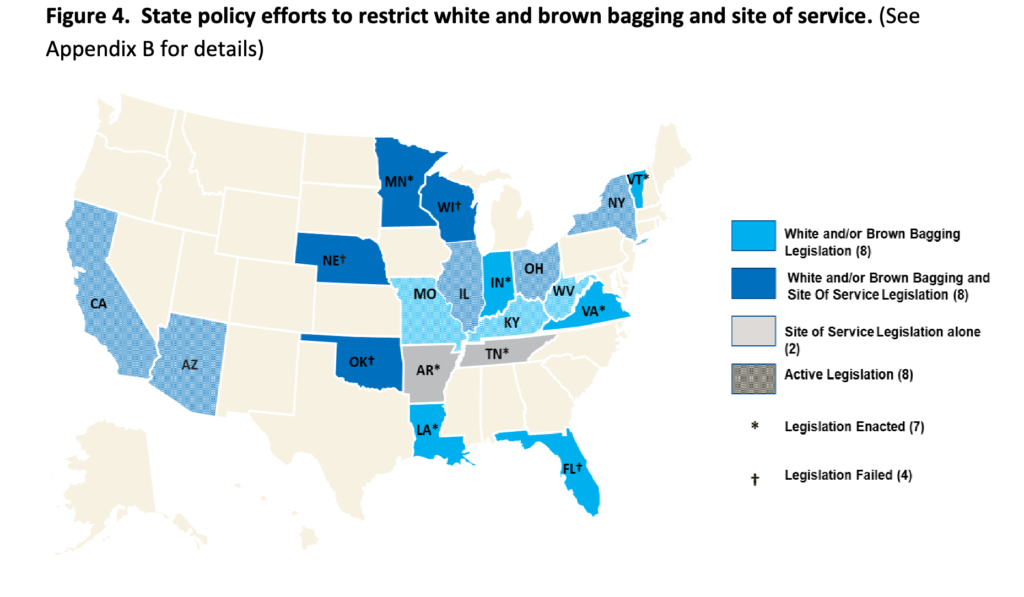

White bagging: Three states (LA, MN, VT) have passed legislation restricting white bagging and nine states (AZ, CA, IL, KY, MO, NY, OH, WV) have proposed legislation that would restrict payer-mandated white bagging

-

Brown bagging. Two states (VA and VT) have implemented policies to prohibit brown bagging. Proposed legislation in three states (CA, IL, NY) would prohibit brown bagging in addition to white bagging

-

Site of service. Three states (AR, MN, TN) have passed legislation prohibiting payers from requiring a clinician-administered drug to be infused at home.