Notifications

ALL BUSINESS

COMIDA

DIRECTORIES

ENTERTAINMENT

FINER THINGS

HEALTH

MARKETPLACE

MEMBER's ONLY

MONEY MATTER$

MOTIVATIONAL

NEWS & WEATHER

TECHNOLOGIA

TV NETWORKS

VIDEOS

VOTE USA 2026/2028

INVESTOR RELATIONS

COMING 2026 / 2027

ALL BUSINESS

COMIDA

DIRECTORIES

ENTERTAINMENT

FINER THINGS

HEALTH

MARKETPLACE

MEMBER's ONLY

MONEY MATTER$

MOTIVATIONAL

NEWS & WEATHER

TECHNOLOGIA

TV NETWORKS

VIDEOS

VOTE USA 2026/2028

INVESTOR RELATIONS

COMING 2026 / 2027

About Me

Latinos Media

Latinos Media Latinos Media provides all types of news feeds on a daily basis to our Members

Posted by - Latinos Media -

on - March 21, 2023 -

Filed in - Salud -

-

745 Views - 0 Comments - 0 Likes - 0 Reviews

That is the question posed in paper by Baker, Larcker and Wang (2022). I summarize their key arguments below.

The validity of…[the DiD]…approach rests on the central assumption that the observed trend in control units’ outcomes mimic the trend in treatment units’ outcomes had they not received treatment. As the authors write:

First, DiD estimates are unbiased in settings with a single treatment period, even when there are dynamic treatment effects. Second, DiD estimates are also unbiased in settings with staggered timing of treatment assignment and homogeneous treatment effect across firms and over time. Finally, when research settings combine staggered timing of treatment effects and treatment effect heterogeneity, staggered DiD estimates are likely biased.

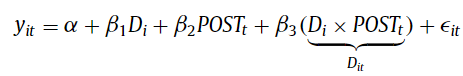

Oftentimes, DiD is implemented using an ordinary least squares (OLS) regression based model as follows:

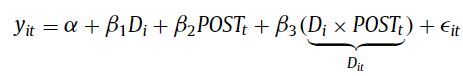

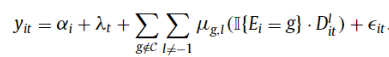

When there are more than two groups and more than and 2 time periods, regression-based DiD models typically rely on two-way fixed effect (TWFE) of the form:

Where the first two coefficients are unit and time period fixed effects. Note that previous research from Goodman-Bacon (2021) shows that static forms of the TWFE DiD is actually a “weighted average of all possible two-group/two-period DiD estimators in the data.”

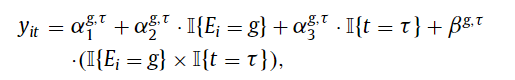

When treatment effects can change over time (“dynamic treatment effects”), staggered DiD treatment effect estimates can actually obtain the opposite sign of the true ATT, even if the researcher were able to randomize treatment assignment (thus where the parallel-trends assumption holds).

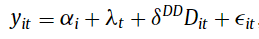

The reason for this is because Goodman-Bacon (2021) shows that the static TWFE DiD is actually consists of 3 components:

The first term is the term of interest. If the parallel trends occurs, then VWCT =0. The last term arises because, under static TWFE DiD, already-treated groups as effectively used as comparison groups for later-treated groups. If DiD is estimated in a two-period model, however, this term disappears and there is no bias. Alternatively, if treatment effects are static (i.e., not changing over time after the intervention), then ΔATT = 0 and TWFE DiD is valid.

The challenges, however, occurs when treatment effects are dynamic. In this case ΔATT ≠ 0 and the TWFE DiD is biased.

So what can be done? The authors offer 3 solutions:

While there has been a lot of math in this post, if researchers apply these alternative DiD estimators, the authors wisely recommend that “researchers should justify their choice of ‘clean’ comparison groups—not-yet treated, last treated, or never treated—and articulate why the parallel-trends assumption is likely to apply”.

You can read the full article here.